Ever since we started officially promoting our retainer for Digital Forensics and Incident Response (DFIR) in 2017, the number of handled cases increased steadily. We have previously presented excerpts of our analysis work in blog posts, such as VPN Appliance Forensics, Docker Forensics, Straightforward Mobile Forensics or The Threat, the Fox, and the Sentinel. Today we will abstract from our effective cases and provide a bit of non-representative statistics on typical DFIR cases that hit our desks.

What is a Typical DFIR Case?

The anonymous data on our cases allows us to answer the question “What is a typical DFIR case at Compass Security?”.

We have crunched the numbers on our latest DFIR cases to arrive at an answer for this question and found: The cases we typically handle are not well expressed by available taxonomy such as the Reference Taxonomy, the CIRCL Taxonomy or the ecsirt.net taxonomy. Now, every DFIR case that lands on our tables is unique and some are hard to categorize. We decided to lay out our latest incidents by a type and a class.

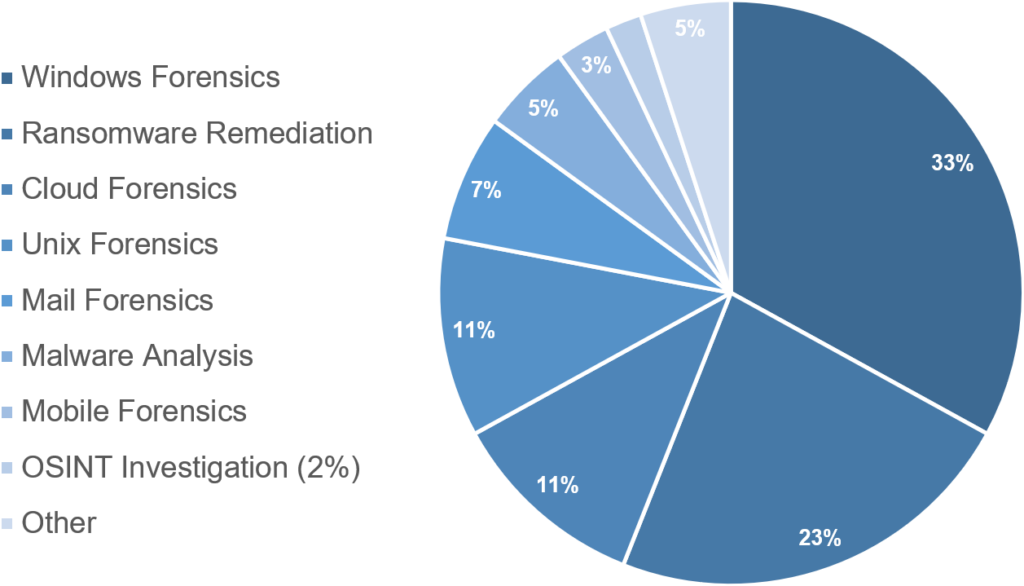

Incidents By Type

The incident type describes the work an analyst was mainly performing during the incident.

Clearly, Windows forensics and ransomware remediation are the most prevalent types of investigation we are currently handling and together make up for more than half of the cases. As the Windows environment is the de-facto standard in our customers networks, this is not too much of a surprise. It needs to be mentioned here, that almost all ransomware remediation cases are attached to a Windows infrastructure as well and many Windows forensics cases are started from what could have developed into a ransomware situation.

However, especially since the time of the pandemic, we have noticed an increase cloud forensics investigations and expect to be handling an even higher number in the future. There are several different classes of cloud investigations, most commonly we investigate M365 credential theft cases and various types of privilege abuse.

We have created a separate type of mail forensics, in which for mainly our business e-mail compromises cases fall.

Malware analysis, mobile forensics and OSINT Investigations only take up a bit more than ten percent of our cases.

The type of incident does not represent the scope and impact of an investigation. This is why we decided to introduce another metric of incident class.

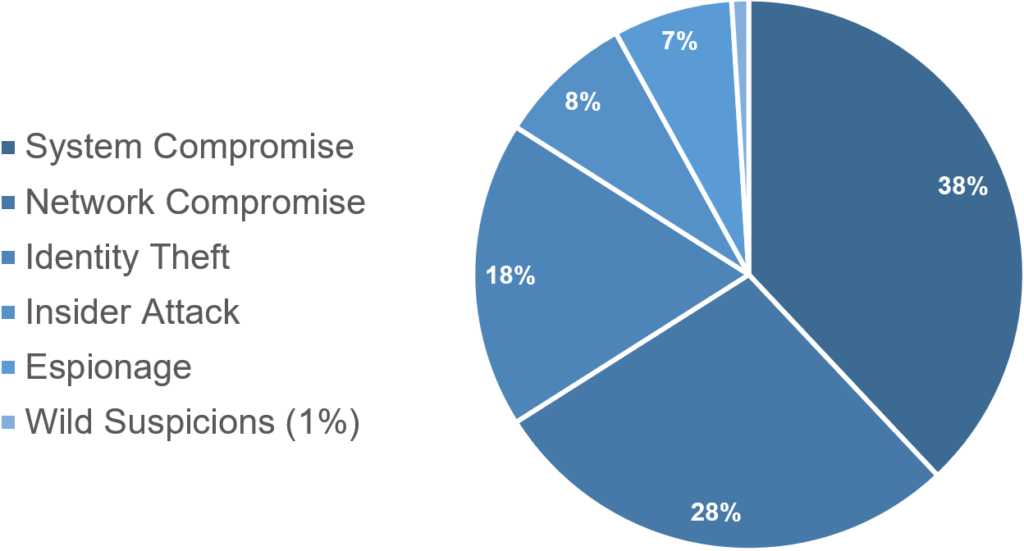

Inidents By Class

The incident class describes an incidents scope, severity, and/or impact.

As the class of incident is not as self-explanatory as the type, there is a short legend provided in the following.

- System Compromise: A single host or small set, such as network segment of hosts was compromised. Most often this is an internet exposed system, DMZ, or the client of a phishing target.

- Network Compromise: A full company network, such as a Windows Domain or similar was compromised. This most often occurs in a ransomware scenario or what probably would have developed into one without the detection.

- Identity Theft: This class includes various types of credential theft and abuse. The most representative accounts stolen are M365 accounts.

- Insider Attack: This class holds all cases, where an employee or connected person is responsible for the incident.

- Espionage: This class incorporates all industrial espionage and spyware cases, such as NSO Pegasus infections.

- Wild suspicions: Now, we could have called this class False Positive, but we felt the term wild suspicions (internally dubbed witch-hunt) better expresses the perception of the analyst in charge of the investigation.

At first, it may come as a surprise that full domain compromises are not the most frequently observed class of incidents – given that modern attackers like ransomware affiliates typically only act as soon as they are in full control of a domain. Still in many of our incidents, a breach was observed in a phase prior to a full domain compromise.

There may be a significant skew in our statistic compared to other cases:

A significant number of incidents originate from retainer customers, where defense, logging and monitoring capabilities are typically assessed and improved in the on-boarding process.

Incidents By Detection

In almost all our cases, our customers have already detected a possible incident through various means and have already performed an initial assessment.

Generally, the detection is one of the more challenging parts of incident response, however, in a high percentage of our latest cases, initial detections are based on quite notable indicators, such as trough:

- money got transferred. A very late but strong lead to follow-up.

- external notice. An e-mail or registered letter of the National Cyber Security Center detailing critical vulnerabilities or compromise.

- for an Antivirus or EDR alert. Mostly based on hacking tools and scripts either dropped to disk or being executed.

- detection of suspicious or known malware behavior. Such as enumerating computers, ports, accounts, shares. This includes detection of connections to known malicious URLs/IPs or known Command and Control (C2) traffic.

- pure chance, often in combination with mishaps on the attacker side. Such as when a system administrator finds a remote access tool on his desktop, a web shell in a webserver directory or a new user folder of the domain administrator on a server where it does not belong.

- an intentionally placed message by the attacker, such as a statement or ransom note. Throughout several cases, we have noticed indicators that could have led to an earlier detection, but were dismissed, disregarded, or ignored. These indicators mostly consist of warnings and alerts of the same detection types as mentioned before.

Conclusion

Our very typical DFIR case is the analysis, containment, eradication and recovery of one or a few devices in a Windows domain.

We may maybe follow-up with trending stats at some later point. However, a quick glimpse at our data reflects a very satisfying sharp drop of reported incidents by March 2022 which then, unfortunately, slowly started growing again in late summer.

Its a small sample set we have and wild speculations in relation with world politic events are left to the reader.

Leave a Reply